The grand challenge: Predicting future morphological changes in a changing environment

The reigning conceptual framework for the mechanism of evolution, laid down almost a century ago, is that evolution proceeds by natural selection for reproductive success among individuals that vary by random nucleotide changes in their genome. However, there are many anomalies, including the rapid evolution of complex structures and the existence of RNA-mediated transgenerational inheritance, called ‘paramutation’. It is also believed that environmental factors cannot induce novel phenotypes.

More than half a century ago, the famous developmental biologist Conrad Hal Waddington proposed the ‘genetic assimilation’ hypothesis in which genomes contain cryptic variation that are selected to produce particular phenotypes for environmental adaptation. Later, Mary Jane West-Everhard proposed that plasticity in response to the environment is the first step of morphological evolution, which provided a non-DNA centric explanation of evolution. However, experimental systems to investigate these proposed evolutionary process were lacking.

Vertebrates have evolved an extensive central nervous system including a brain, a complex facial structure, and a motile tail that enabled them to expand into habitats all over the planet. How and where did they originate? This has been a central question for evolutionary biologists for more than a century. Invertebrate chordates, such as tunicates and amphioxus, have notochords and central nervous systems, but they do not have an elaborated brain nor neural crest cells that give rise to jaws and related facial structures. The evolutionary process behind these huge advances in vertebrates has never been explained by the theory of natural selection by random mutation, but may be explained by the an interplay between the plasticity of gene networks that govern the development of vertebrate morphological and neuronal characteristics and inheritance.

The key questions are:

- Do we find plasticity in gene networks that explains evolution of vertebrate characteristics?

- What brings plasticity to developmental system?

- What is the mechanism of the fixation and inheritance of gene networks that are induced by the environment?

Since early embryogenesis is mostly governed by RNAs provided by the mother, but not the DNA of the embryo, our hypothesis is to test maternal provision of RNA facilitates plasticity of gene network and inheritance of modified gene network by the environment.

We test these hypotheses using tunicates as simple model of chordates to to study the origin and the evolution of vertebrate novelty. Tunicates are the closest invertebrate relatives of vertebrates, showing a notochord, central nervous system and motile tail. It does not have a clear ‘brain’ comparable to vertebrate brain, but has ganglions instead. Tunicates also do not have neural crest cells, that give rise to facial structure of vertebrates. We hypothesize that plasticity in gene network to environmental stress, such as thermal stress, facilitated the emergence of novel gene regulatory networks that gave rise to vertebrate characteristics by integrating environmental input. To this end, we compare gene expression datasets from sibling species of tunicates that are adapted to different thermal environments.

We are also interested in the role of the mother in changing evolutionary process. For more than a century, many people believed that maternal RNAs are transcripts of maternal genome in the egg. However, we suggest that maternal RNAs produced in response to the environment are transmitted through the mother. To test this, we use surrogate fish technology that replaces mothers to see how mother can modify maternal provision of RNAs and impact on the phenotypic variation in the next generation.

1. Mechanisms of maternal effect in developmental buffering

Developmental buffering, a biological system that buffers impact of genetic as well as environmental variation, is a key to understanding how organisms change during the evolutionary process. Previous studies suggested various molecular as well as network aspects of developmental buffering. Most famous examples are studies on Hsp90, heat shock protein, and theoretical studies in gene network. We have been investigating the molecular basis of developmental buffering using sister species of the ascidian genus Ciona. These two species lives in different temperature regimes. By heat shock experiments, we found a tremendous difference in the level of developmental buffering under temperature perturbations between the two speices (Sato et al. 2015; Fig. 1). Using cross-hybridization of these sister species, and comparative transcriptomic studies, we discovered the importance of endoplasmic reticulum-associated chaperones in developmental buffering (Sato et al. 2015) instead of Hsp90. ER associated chaperones had not been a subject of studied in developmental biology by then. Since ER chaperons are involved in both protein folding as well as in degradation pathway, we proposed that both protein folding and degradation are important in developmental robustness (Sato 2018). We also tested this hypothesis by RNAi screening in C. elegans (Hughes et al. 2019; Fig. 3). The idea has now been supported in various other developmental models such as in segmentation clock.

We have also been investigating network characteristics of developmental buffering. First, we tested how the developmental gene network is linked to developmental buffering, since how the spatiotemporarily dynamic process of development is stabilized by developmental buffering has been a matter of debate. A difficulty of studying Ciona is, despite the fact that they are chordates, finding gene ontology with the human gene model is impossible in approximately 20% of all gene. In addition, there is no protein-protein interaction network has been identified. We exploited weighted gene correlation network analysis (Horvath and Dong, 2008) to make sense of such transcriptomes. The analysis confirmed several important characteristics of buffering that have been previously shown experimentally in yeast and worms, for example being composing of genes with high connectivity, suggesting that the analysis correctly predicted the buffering network. By calculating similarity of gene expression between buffering genes and developmental genes, and comparing them with the similarity between buffering genes, our analysis revealed that developmental gene networks are loosely linked to developmental buffering. Yet the link contains signaling molecules that are key in developmental patterning, we propose that stabilization of signaling molecule is the key in developmental buffering (Sato et al. 2022).

- Fig. 1

- Fig. 2

- Fig. 3

2. Origin of, and transgenerational changes in variation in the face of thermal challenge

Whilst developmental buffering stabilize development thereby maintains species, morphological change requires reduced level of buffering. What alters the level of buffering and how does it affect variation? I hypothesized that a key mechanisms is the influence of maternal environment on the level of buffering in the offspring (Sato 2018). To address this, we investigated transgenerational impact of thermal stress on variation in maternal mRNAs in eggs by thermal challenge of the mother during her development. We found that the variability of maternal mRNAs decreased in the F1 generation but our data showed a possibility of increase in variability in the following generation (Sato et al. 2024). We are currently working on epigenomic impact of thermal stress in the evolution of chordate body plan using epigenomic sequencing and mathematical modeling of gene expression changes.

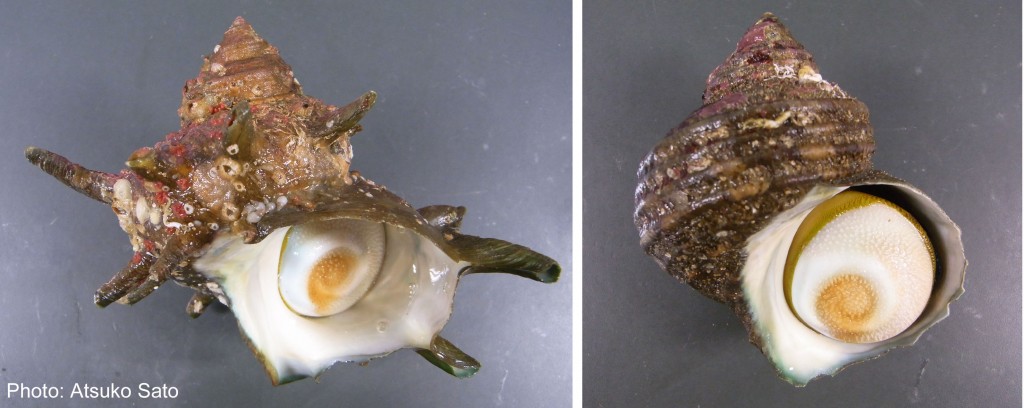

3. Mathematical modelling of phetnotypic plasticity in the horned turban snail Turbo sazae.

Phenotypic plasticity is the phenomenon of organisms showing different phenotypes depending on the conditions. Traditionally phenotypic plasticity is considered as a cause of morphological change in the evolutionary process, yet this has been open to debate. We aim to predict the pattern of organismal change by creating a multi-scale mathematical model that connects molecular-level change in a cell and structural change at the tissue level to morphological change using a fascinating example of phenotypic plasticity in the horned turban. T. sazae is a gastropod species that lives in Japan and South-East Asia. Within the single species, there are individuals with large horns or no horns (Fig. 4). A single individual may even switch between horned and non-horned during its lifespan. Previous ecological studies suggested that wave strength is a switch for the presence and absence of horns. Using mathematical modeling and machine learning, we found that spine phenotypes can be described by different mathematical models by assuming molecular reactions that underlying spine formation (Moulton et al. 2024).

4.Biology of pterobranch hemichordates

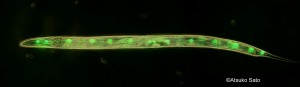

Hemichordates are important organisms when we address questions of our origins and the evolutionary process. Amongst the two groups of hemichordates, acorn worms (Fig. 5) have advanced our knowledge in developmental biology of hemichordates, whereas our biological knowledge of pterobranchs (Fig. 6) is still poor. Using a population of pterobranchs from SW England, which can be collected relatively easily from shallow water, we conduct developmental, ecological and evo-devo studies on the origin of vertebrates and the evolutionary process.

- Fig 5

- Fig 6